Stopping Terrah’s Heart — 12 Times

Published February 2020

Trailblazing Procedure for AVM Gives Mother Her Life Back

Motherhood has always been important for Terrah Cummins. She and her husband, Christopher, had two beautiful children, a boy and girl, and were enjoying the ups and downs of parenting.

Then a brain hemorrhage threatened to take it all away. There was a noticeable absence in her children’s lives while Terrah fought for her own life. “Looking back, it hurts,” Terrah says. “I just disappeared one day, and they didn’t know why.”

Fortunately, her care team at Northwestern Medicine was determined to make sure her children didn’t lose their mom. The team just needed to stop Terrah’s heart — 12 times.

Diagnosed With an Arteriovenous Malformation

The day the brain hemorrhage struck, Terrah began experiencing a headache that she says felt like fire going up the back of her head. She felt some relief after taking an aspirin, and that’s all she can remember.

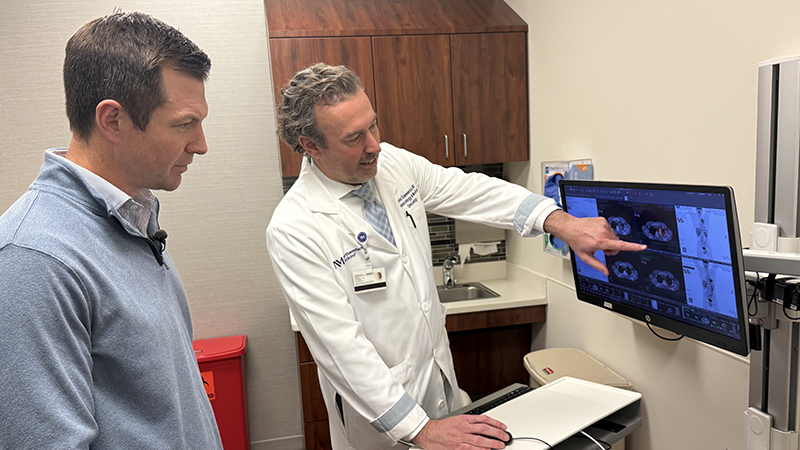

“She had a significant brain hemorrhage,” says Babak S. Jahromi, MD, PhD, the vice chair of neurological surgery at Northwestern Medicine. Imaging determined Terrah had an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), or an abnormal tangle of blood vessels in the brain.

“It was dormant for many years, and only started to declare itself over the last year,” says Michael C. Hurley, MD, neurointerventional radiologist at Northwestern Medicine. Over time, this fragile tangle of blood vessels can cause pressure to build up, interrupting normal blood flow. If the pressure becomes too great, the AVM can rupture, causing serious, life-threatening brain damage.

It’s not going to work unless you stop the heart and the blood flow.— Babak S. Jahromi, MD, PhD

Every Heartbeat in the Room — Except Hers

Traditionally, to treat an AVM, the neurosurgeon would perform surgery to remove it. But Terrah’s AVM was in a dangerous and difficult to reach location in the brain. A less invasive method to reach her AVM would involve inserting a catheter into an artery and threading tools through blood vessels, in the direction of blood flow, to the AVM to inject a glue-like substance to block off blood supply. This is done via a process called embolization. However, in Terrah’s case, there was not a safe access point through her arteries to reach the AVM, so this type of procedure wasn’t an option either.

Instead, Terrah’s care team considered coming from the opposite direction, through a vein, against the blood flow. “There’s one problem: It’s not going to work unless you stop the heart and stop the blood from coming at you,” says Dr. Jahromi.

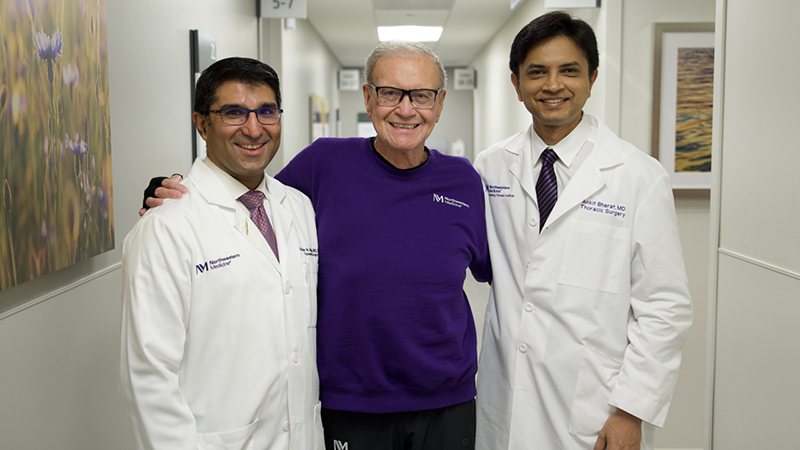

The team turned to Bradley P. Knight, MD, cardiac electrophysiologist at Northwestern Medicine. “We’re comfortable doing this in patients for 10 to 15 seconds,” Dr. Knight explains. But Dr. Jahromi and his team needed 45 seconds — in multiple increments. “To protect the brain, we had to induce the deepest level of anesthesia that is possible. Brain activity was as close to the flat line as it could be,” says Northwestern Medicine Anesthesiologist Ljuba Stojiljkovic, MD, PhD. “You could hear the heartbeats of any person in the room, except the patient’s, because we silenced it — not once, but 12 times.”

As for Terrah, she felt at ease when it came time for the procedure. She says, “I just closed my eyes and started hearing a song in my head: ‘I’ve got confidence, so much confidence, in you.’”

Despite the unusual approach and intensity of the surgery and anesthesia, the process went smoothly and was deemed a success.

Terrah says she never lost her faith throughout her journey. Instead, she continues to be grateful for being gifted with life. “It doesn’t make sense why I’m still here,” she says. “It’s a wonderful blessing.”